Affirming Neurodiversity in Therapy and Education

I first learned about neurodiversity while reading In a Different Key: The Story of Autism, where it was described as a movement for those who choose to celebrate their neurological differences. The concept resonated with me because it aligned with my personal truths and observations as a provider, therapist, and advocate working with hundreds of autistic people and families. I noticed that something was off in how neurodiverse people were approached and treated by their communities. Teenagers told me how much they struggled with therapists because they felt manipulated with rewards to do things that caused them distress. There was no respect for autonomy. A teenager attending private school noted the irony that he was reading The Scarlett Letter in English class while carrying a behavior recording point sheet from class to class. “Low functioning” adults were greeted with Cheshire Cat smiles and spoken to in sing-song voices. There seemed to be an overt hierarchy and a sense of superiority, with neurotypical people firmly placing themselves above neurodivergent, which was particularly glaring in what was supposed to be the helping profession. I felt like I was resisting much of the formal training, which typically focused on compliance and modifying behavior to make life more comfortable for everyone except the person in “treatment.”

The more I learned about neurodiversity, the more I aligned with the philosophy and the more I wanted to share it with others. The concept was simple enough and congruent with much of what I had already learned from years of reading existential psychology, positive psychology, attachment theory, and person-centered theory. My beliefs cemented when I learned about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which emphasized clarifying individual values, setting goals to move toward those values, and mindfulness to increase self-awareness and improve self-regulation.

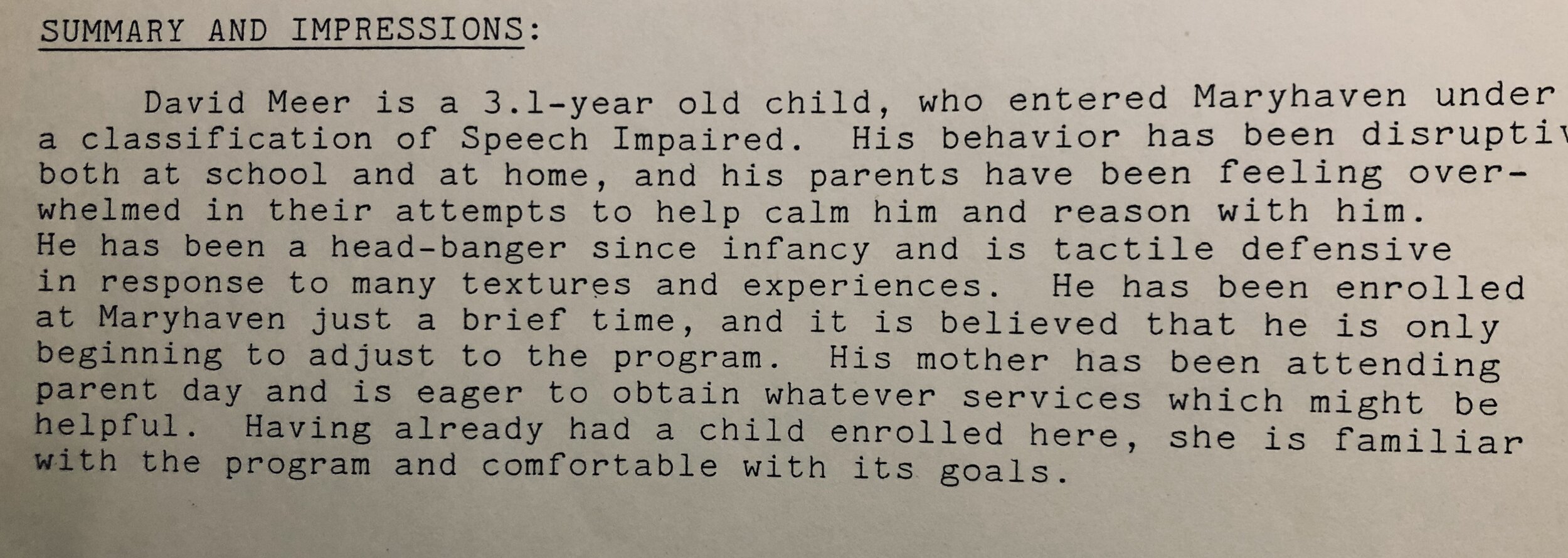

It all made sense because this philosophy is what allowed me to thrive in spite of the many struggles I faced as a neurodivergent child. I self-soothed by banging my head against brick walls and pillows, what I later learned was stereotypic behavior. I lined up Matchbox cars and exhibited “compulsive and obsessive play patterns.” I struggled with pragmatic and expressive speech, “scripted,” was identified as “speech impaired,” and prescribed speech therapy up to four times per week during my pre-school and elementary school years. I was inattentive and unable to follow directions. I would respond to questions seemingly at random in what was described as “free association,” though the connections made sense to me. I was hyperactive, jumping on desks, blurting out, and being told in nearly every report card (which my mother saved) that I was “challenging” or “difficult” to manage in the classroom. I was described as “tactile defensive in response to many textures and experiences” and struggled with sensory processing. I was overstimulated by my environment. I only wore socks with colored stripes and would not wear new shoes. I didn’t like when the weather changed, which would require me to adjust my wardrobe for the season. I had dreams about numbers and collected statistics in an endless collection of salt and pepper notebooks. I walked on my toes. I was prescribed weekly play therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, and given one-on-one instruction to help me focus.

I had a hard time fitting into societal expectations because of my differences.

I hated school until fifth grade, when my teacher noticed my strengths and encouraged me to be more of who I was. She placed me in an advanced math class, increased my time in art class, identified and supported my interest in Goosebumps, and helped me construct my own pieces of writing. I also found acceptance from my peers, including a really cool girl who appreciated my eccentricity, and suddenly found myself part of a social group for the first time in my life. I had an opportunity to connect with the world in a way that made sense for me. As I navigated the complexities of high school, college, graduate school, and the workplace, I noticed I could thrive when placed in environments where my talents were maximized and my voice was valued, but became exhausted, bored, and disengaged when stifled.

Unfortunately, not everyone is given an opportunity for self-exploration and growth, to be considered as a whole person, and to have their natural curiosity of the world fostered and appreciated. My aim is to help transform how we view human thinking and behavior, to move toward a position of curiosity and acceptance, to be expansive, and to encourage a world where we listen to create understanding.

So what is neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity is a portmanteau first coined by activist Judy Singer and columnist Harvey Blume, which can be broken down into its components of “neuro,” referring to the nervous system, and “diversity,” which refers to the variety and differences of things. Hence, neurodiversity speaks to the variation in neurological functioning in the human race. The neurodiversity movement urges us to recognize neural and biological differences, to understand that not every brain works like yours, and that other people may experience the world much differently from you. There are different ways of perceiving the world, capacities to reason and think critically, and sensitivities to environmental stimuli.

While our brains are distinct, they are also remarkably similar. Physiologically, brains are nearly identical – gruesomeness aside, you would not be able to tell the difference if I placed mine and yours on a table next to each other. We have the same building blocks, so while there are infinite combinations and no two humans can ever be exactly the same (even identical twins are markedly different), there are biological constraints on what a human can be. Brains are made up of the same regions and have the same neurochemical processes. All brains have the same basic function – to operate the body.

However, no two brains operate in the same way. Neuroplasticity tells us that brains undergo change in response to their environment, adapting, and reorganizing by forming different patterns of neurochemical reactions. If your brain is an engine for the body, then these reactions are the spark. Each human has its own pattern of connectivity - how it’s “wired.” These patterns of neurological organization are what make your thinking uniquely your own.

Brains have different volumes, amounts of gray and white matter, and rates of change and development. The brain can change in response to its environment, which is glaringly true for those who have experienced a traumatic brain injury. But there are more subtle ways in which the brain changes. Exposure to trauma, such as veterans returning home from a horrific war, can significantly change the structure of your brain. Meditation can change the structure of your brain. Exercise, too. It is probably safe to assume that everything you encounter leads to structural changes in your brain and there are infinite ways in which your brain can adapt and reorganize. Your brain has a unique way of functioning at any given moment in time and is the result of your distinct genetic makeup and personalized environmental exposures. Your brain is sort of in the middle of its own coming of age story, adapting, learning, and changing. This evolution is a common experience for us all.

Why does neurodiversity matter?

Diverse societies that work together can be more responsive to demanding environments. Steven Covey talks about the idea of “synergy,” Habit #6 in his seminal work 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, which indicates that substantial diversity leads to better problem solving and that “two heads are better than one.” Deep-level diversity workplaces have been shown to be more productive, innovative, and creative. They are inclusive, which increases access to a larger talent base.

We need to put neurodivergent thinking into context. Although a particular way of thinking could seem odd and perhaps appear unhelpful right now, in this particular environment, on this problem we are trying to solve, does not mean it will always be that way. What may be considered a mental illness by our present societal standards may have been valuable in another time and/or place. Thomas Armstrong suggests that individuals diagnosed with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder would have been highly valued during hunter-gatherer times. What may be considered a learning “disorder” may be reframed. For instance, it appears that over a quarter of American and British CEOs have a learning difference – dyslexia. Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad attributes his success to his unique abilities as a dyslexic person. Temple Grandin thinks Albert Einstein and perhaps Steve Jobs would have been diagnosed with autism. For humans to progress, we need a variety of people in a position to maximize their strengths. If we only had social butterflies who didn’t like to work with their hands, it would be unlikely we would have built a city that looks like this:

People who adhere too closely to social norms can be easily influenced, so it is also important to have divergent thinking to protect against social manipulation. Typical isn’t always the right way of being and thinking. Fusion to cultural norms can take away individuality. Groupthink is the enemy of originality. This is not to suggest that we should always move away from cultural norms, because they often have adaptive purpose and improve group cohesion, but we need to know when to challenge “expected behavior” and to call out arbitrary, unhelpful, and potentially harmful social norms.

What are some of the current social norms and cultural expectations?

A society needs expectations of its members in order to harmoniously function. Humans need to cooperate in a complex environment for survival. The behavior we cannot accept is one that causes harm to others or themselves, an idea reminiscent of the Hippocratic Oath. We can also consider the platinum rule, which tells us to “treat others the way they wish to be treated.” Let us also consider the unalienable rights – life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These are some insightful ideas about human interaction and freedom.

Unfortunately, sets of seemingly arbitrary rules for behavior in a society also emerge, our “social norms,” which dictate what is acceptable and what is not. Although there may be valid logic and reasoning to explain how some of these rules emerged, many remain superficial yet carry heavy social consequences. Here are a few:

Americans value eye contact. Temple Grandin notes that autistic people have brains that react in the opposite manner. So the feeling for an autistic person when engaging in eye contact is how a non-autistic person would feel not engaged in eye contact. Eye contact for an autistic person can be painful. Eye contact is not valued in Finnish and Japanese culture.

We value socializing and relationships, but have negative thoughts about material attachment and objects. Sometimes an attachment to an object is seen as awkward. Why is it acceptable to place symbolic meaning on some things (a cross, book, wedding ring), to hold them in reverence, and not other things (action figures, healing crystals, sticks).

We value focus and stillness rather than movement and hyperactivity. Hyperactivity may have been valued with nomadic hunters.

We value formal education and the “three Rs” of Reading, wRiting aRithmetic, though these processes are minimally helpful in visual arts.

We value verbal language for communication, though much of our communication is expressed non-verbally.

We value literacy, though some estimates indicate nearly 1 in 5 are illiterate.

We value extroversion over introversion, in particular, people who can engage in small talk. In fact, it’s expected of you. You are expected to ask “how are you?” though you are not seeking an expansive response.

Stimming is seen as awkward and inappropriate, but other behaviors, such as waving your hand to say goodbye, dancing to music, and clapping hands at a golf tournament are socially acceptable because of the context. These are arbitrary rules of decorum.

We value stoicism and oppose behavior that is considered “challenging” or “difficult.” Strong emotional reactions are considered an issue. Those who are too “emotional” have a problem and could be labeled histrionic. Those who weep in public are shamed. There’s no crying in baseball. Yet, the Greeks considered weeping a virtue and in the 1600’s we valued sadness and viewed it as a transformation process.

America has a history of attempting to switch handedness for lefties.

There are arbitrary rules for shaking hands across cultures.

We have entire courses dedicated to dining etiquette, including how to choose the correct utensil and how to properly order a class of wine.

You are expected to live independently and considered a failure if you need additional support.

Since these rules can be arbitrary, we need to challenge them and allow for divergent ways of functioning. Typical doesn’t necessarily imply “correct” or even beneficial. Who defined what is “normal” anyway? Applying judgment toward atypical thinking and behavior often leads to feelings of shame and fracturing of the self. Subtle insults, such as “wow you’ve done so well for an autistic person” implies a sense of superiority in ability. These judgments and microaggressions have the potential to stifle growth. Neurodivergent people have to be twice as perfect to be considered half as good.

Living in a neurotypical world already exacerbates many daily living challenges, so assumptions that a neurodivergent person cannot live independently, has an intellectual disability, or is socially inept, harms their ability to live a fulfilling life. The result is that many neurodivergent individuals will put on the social mask and expend immense amounts of energy to conform their individual expression to the expectations of arbitrary societal standards. The message is clear: How you think does not work here; you are too different; think and behave like this; conform. If you think or behave differently from the social norms, you run the risk of being labelled as crazy, mentally ill, and disabled.

This is neurotypical ethnocentrism.

Ole Ivar Lovaas, a pioneer of applied behavior analysis (ABA) and discrete trial training, aimed to make autistic people “indistinguishable” from neurotypical peers. The infamous 1987 study indicated that “children … received 40-hours per week, and the treatment lasted two-to six-years. The outcomes indicated 47% of the children … became indistinguishable from their peers … were able to have their “autism” label removed.” It is absurd to believe that behavior modification changed genes and brain chemistry enough to remove someone’s autism. The result is more likely masking of autistic qualities due to reinforcement and punishment strategies. I’m not sure that’s an appropriate goal for every autistic child. Ultimately, the message, intentional or not, is that autistic thinking and behavior is wrong. Autistic communication, play, movement, and emotion is abnormal, and needs to adjust to fit in with the neurotypical community.

Autism Speaks sends a similar message.

The message is again clear: autism is a disease and we should aim to prevent it when possible. The sentiment is reminiscent of my growing concern in Europe, where prenatal blood tests are used to screen for Down’s syndrome, leading to a significant increase in abortions. Iceland has nearly eradicated Down’s syndrome from the population. My concern is that brain differences are viewed as diseases to be eradicated, even prior to meeting the person, because of stigma.

Compliance and Assimilation

The expectation is that neurodivergent people will assimilate to societal standards or risk exclusion and possible social ostracization. The most creative, divergent thinking students are typically the least liked by their teachers. Therapies have emerged that aim to target “undesirable” behavior and replace with something more socially acceptable. On the surface, this may be sensible, because it is important for people to understand what behaviors are typical and which are not, and how to navigate this complex system when interacting with the world. However, many therapies use strategies to manipulate behavior without considering how the individual views themselves or the powerful internal struggles.

The practice is particularly nefarious because it targets children, who are unable to consent to treatment. They do not have the right to refuse. Let’s also consider that the model of comprehensive applied behavior analysis calls for twenty-five to forty hours a week of therapy, which essentially equates to a full-time job. The expectation is that children will comply with the therapy, or be ignored, not have an opportunity to “earn” tangible and social rewards, and even have their caregivers withdraw in a process called “planned ignoring.” If behavior is communication, and the aim of the helping profession is to listen to create understanding, then how can it be acceptable to literally turn our backs on a screaming child? Because the function of behavior is “attention-seeking?” Because we don’t want to reinforce “undesirable” behavior of tantrums? And what happens when children choose to behave only to earn the reward rather than forming a set of values? Autistic adults have indicated that the most helpful intervention would be skills for managing difficult emotions. Instead, they are taught to camouflage their emotional reactions, which may lead to learned helplessness and activation of the dorsal vagal pathway. Mona Delahooke, Ph.D, tells us further that “When human beings feel ignored, it degrades the social engagement system.”

Autistic adults are speaking out against this form of therapy, something that you rarely encounter with other treatment modalities. I do not know of many other therapies that have received as much backlash, to the point it is being labeled as abuse and traumatic. Autistic adults are urging us to reconsider how we deliver therapeutic services and the potential long-term consequences. Opponents of applied behavior analysis suggest that it can lead to prompt dependence, individuals who are conditioned to obey without questioning, loss of intrinsic motivation, decrease in self-confidence, and learned helplessness. A growing concern is fear that this form of therapy will exacerbate exposure to violent crime and sexual assault. Further research is needed, but these concerns need to be explored and addressed.

It is equally important not to simply dismiss behavior analysis - it is too valuable a science to ignore. Many of the principles are derived from sound theory and years of empirical research. There is no questioning that operant conditioning is an effective means to change behavior. It is important for us to understand how the environment impacts our thoughts, mood, and behavior. We should understand how sensory input impacts us so we can be prepared. We should understand the impact of operants on our future behavior. Knowledge of these systems can empower us to manage ourselves in response to the world and seek out accommodations as needed.

Understanding the foundations of behavior modification allows us to be intentional in how we develop our children. However, I just cannot bring myself to administer external rewards of cookies and candy to influence behavior. It’s demeaning to hand children Skittles one at a time under variable ratios of reinforcement during discrete trial training. It seems particularly diabolical when you consider the impact of candy on the dopaminergic system.

The issue in many behavior programs is external locus of control, in which adults are always in charge of administering reinforcement, and the use of tangible rewards, which decreases interest and spontaneous engagement. Carol Dweck proposes an alternative way to administer reinforcement through praise of effort, critical thinking, and process, which leads to increased confidence and courage. We should be specific and genuine with our praise, which will ultimately encourage the development of intrinsic motivation. The aim is to reinforce strengths and interests one already possesses and to facilitate growth within the individual’s own values system. We must be careful not to administer excessive tangible rewards when something is already intrinsically motivating, since this has the potential to be counterproductive and decrease interest.

We need to expand on behavior analysis and in my opinion, merge the science with other modalities, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Attachment and Polyvagal theories, and Positive Psychology. In fact, some board certified behavior analysts (BCBA) are implementing ACT-based programs, such as Promoting the Emergence of Advanced Knowledge (PEAK), in their practices, which I believe represents a paradigm shift in the philosophy of behavior analysis. This brand of ABA is far removed from Lovaas method, which used punishment techniques such as slapping children in the face. PEAK still uses discrete trial training procedures, but the field of behavior analysis is evolving, so let’s consider how to continue this evolution.

Emphasize strengths and inclusion

The neurodiversity movement promotes identification and building of individual strengths. Thomas Armstrong talks about “niche construction,” where an individual is matched to a supportive environment that will enable them to realize their potential. It aligns strongly with Carl Rogers’ and Abraham Maslow’s notion of self-actualization, the realization of our full potential and authentic selves. Our objective as helpers is to facilitate rather than direct growth.

There needs to be a shift in how we view neurodivergent people in the home, classroom, workplace, and community. Neurodiversity provides civilization with a range of perspectives in life, a variety of styles of living - a multiplicity of possibilities. Judy Singer said “It is important to enable people to use their abilities and talents to support themselves.” Tools such as the CliftonStrengths and Values in Action can help identify strengths to build insight and live out a valued life. The Strong Interest Inventory can further elucidate our interests and direct us toward careers that match up with our interest profile. We can minimize disabilities and maximize abilities through this approach.

Our classrooms should aim to emphasize inclusive learning with opportunities for alternative learning styles. Thomas Armstrong tells us that “children in special education classes tend to be weakest in things that schools value the most - reading, writing, arithmetic, rule following, and test taking; and strongest at what is valued least - art, music, nature, physical skills. They become defined by what they can’t do rather than what they can do.” Classrooms should be designed with a student-centered focus to accommodate vast learning differences and needs. We need individualized and customized curriculum using an ipsative assessment approach. Our education should be holistic, emphasizing the whole person, and foster the natural curiosity of the learner. We want to ensure all students are given access to learning opportunities. We should look to autistic teachers and read first-person accounts to gain insight on how to provide helpful instruction for neurodivergent learners.

Our therapy programs need to shift away from the disease model, which pathologizes neurological differences. We need to emphasize neurodiversity, curiosity, and holism. Our therapies should identify family and individual values, such as in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, before implementing a service plan. Our goals should be primarily focused on the needs of the neurodiverse individual. We should follow the advice of neurodivergent adults in the community, who tell us that they need help with anxiety, depression, self-esteem, making and keeping friends, living with sensory issues, bullying, choosing a career, accepting change, and feelings of disconnection. The SCERTS model emphasizes social communication, emotional regulation, and transactional support. The Gottman Method, Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), and Mindful Parenting can improve communication and emotional regulation within the family. We should encourage physical activity and play, which promotes frontal lobe development and cognitive functioning. Play is the foundation of many relationships. Plato once said “you can discover more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation.” The Floortime model and Early Start Denver Model are child-centered play therapy programs that focus on building relationship through natural scenarios and interactions. Pivotal Response Training is a “naturalistic intervention” that emphasizes underlying motivations and child choice, typically through play. We should help build structure and consistency for neurodiverse children, establish healthy sleep-wake routines, and educate about nutrition and how the food we eat impacts our neurological functioning. We should approach parenting as a process to promote healthy brain development.

I’m still learning a lot about myself and my place in the neurodiversity community. Let’s expand on our understanding by taking the time to listen to each other. It is through listening, this act of love, that we can expand our knowledge and grow together. The first step is awareness. Hopefully this post has provided some insight into neurodiversity. However, this is not an exhaustive post and merely scratches the surface. Please take a look at my Neurodiversity Appreciation page for additional resources, including videos, book recommendations, first-person experiences, articles, and guides.